Posted by Sam on Jan 22, 2013 at 06:24 AM UTC - 6 hrs

A greedy algorithm is an algorithm that follows the problem solving heuristic of

making the locally optimal choice at each stage with the hope of finding a global

optimum. In many problems, a greedy strategy does not in general produce an optimal

solution, but nonetheless a greedy heuristic may yield locally optimal solutions

that approximate a global optimal solution in a reasonable time.

What does a greedy algorithm look like?

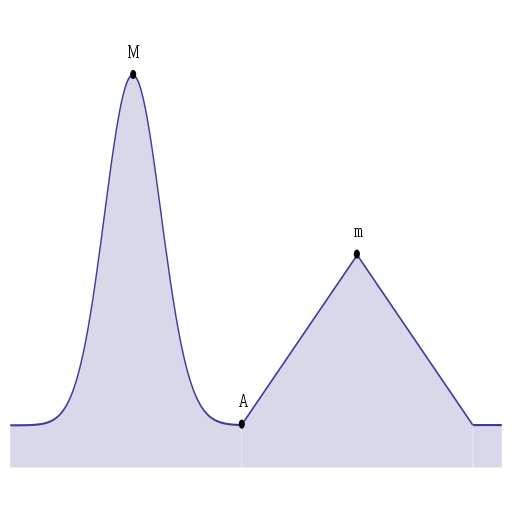

Images from Wikipedia illustrate the concept well. In the first one,

we begin our search of the space for a maximum at point A. If we're greedy, the next

highest point takes us along a path that maximizes at point (lower case) m. However, the

optimal solution is at point (upper case) M.

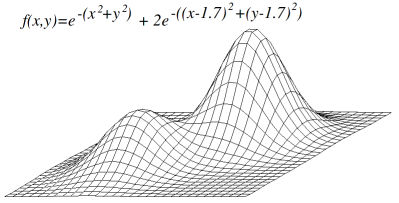

If you're greedily searching (again, for a maximum) in three-dimensional space, and start in

a poor position (like near the left in the image below), you'll never make it off the shorter hill

onto the taller one:

More...

What does a greedy algorithm for yourself look like?

What does a greedy algorithm for yourself look like?

Perhaps we should first define what it is for which we're optimizing: To keep it

simple, I'm going to identify it as maximizing income.

You could also be seeking to minimize the distance (in time) between working for clients,

or minimizing the time you spend acquiring each customer -- maximization is not

an intrinsic property of optimization.

I purposefully exclude things like time and happiness (or optimizing for some

combination of all three). While I value those things and would like to think I've

tried to optimize for them, upon closer inspection I recently realized I've tended

to simply accept whatever side-effect optimizing for money has had on those values.

I think it's a fair assumption that plenty of other people are doing the same. If you're

not one of them: congrats! But before you dismiss the idea entirely, you ought to consider

that you might be, just to be sure.

So what does it look like? Again from Wikipedia, I like the idea of moving from node to node

on a graph:

At each point in time (a vertex on the graph) we are presented with a series of options whose positive

return is the value at that vertex. The options available to us are connected by the edges.

(You might also assign a cost to each edge, and change your greedy-optimization heuristic to be

return minus cost).

In the graphic I've used, only two options are available at each point, but in reality there

are normally a lot more options from which to choose, and maybe even times when you have only

one option.

If we're starting at 7 and being greedy in our search for a maximum, we miss out on the global maximum.

You might mention -- hey, we could backtrack and search the entire space. But you might not

have the resources available once you've gone down the path to 6. You might have reached your

maximum workload by that point, and by the time you free up some time, the opportunity for the 99

is gone.

How do you know if you're running your business like a greedy search algorithm?

Here are some symptoms:

- Taking the first job offer or client you get when you need work

- If you're a freelancer, filling all your time with client work

- Taking the first business model that seems to be working and trying to maximize it

Can you think of any others?

Prior to last year, I was executing a totally greedy algorithm with regards to my career.

But it's not just something I've noticed in myself: almost every job I've had

utilized greedy methods for making money.

As part of my greedy search (which was not just about maximizing money, but more towards minimizing

unemployment, even if it meant working for people who would end up stiffing me on paychecks),

I ended up burning through about four months of savings (I had six). Last year

though, I started making some changes to a better approach. When I made my way back up

to a six month cushion and took time to reflect on some of the changes that got me there,

I realized the parallels to algorithms I'd learned about in college.

Improving your odds

How can you improve your chances of finding a global (or at least higher) maximum?

In the general problem, given enough time and resources, you could do an exhaustive search -- or in our

graph model, visit every node.

But I don't have the resources to exhaustively search the entire space to produce an

optimal solution, and I'm betting you don't either.

Instead of straight greedy hill-climbing, we could explore

some variants.

My favorite here is called "shotgun hill climbing," where instead of following a path all the way

to it's maximum, we'll randomly restart (but we don't forget where we came from on

those restarts, in case we don't end up in a better position).

It's what I like about Amy Hoy's stacking bricks

metaphor. A freelancer can start taking time between gigs (or not remain fully engaged) and spend

some time developing products. Each successive product is a new brick, and over time

you can build a wall.

Savings and product revenue are like ammunition for your shotgun hill climbing business

algorithm. They allow you to explore different starting positions, as long as you're not

being greedy with minimizing the distance (in time) between clients or booking all your time

to work for others.

In practice, all those ideas you have floating around in your head (or ideas.txt file)

are the different options you have in paths to take (in addition to other jobs, clients,

ideas for "upselling", etcetera). You have to spend a significant piece of time on one

to find out if it gets you further up the hill or not -- but not so much so that you can't

get back to your last local maximum or randomly try another.

(Side note: I'm not advocating strictly random

here -- you can apply some heuristic to affect the "probability" of choosing a certain idea).

Last year I took my first steps to taking a shotgun approach. This year I plan to take it further.

Thoughts? I'd love to hear them below.

Hey! Why don't you make your life easier and subscribe to the full post

or short blurb RSS feed? I'm so confident you'll love my smelly pasta plate

wisdom that I'm offering a no-strings-attached, lifetime money back guarantee!

Posted by Sam on Jun 30, 2011 at 04:40 PM UTC - 6 hrs

I was introduced to the concept of making estimates in story points instead of hours back in the Software Development Practices course when I was in grad school at UH (taught by professors Venkat and Jaspal Subhlok).

I became a fan of the practice, so when I started writing todoxy to manage my todo list, it was an easy decision to not assign units to the estimates part of the app. I didn't really think about it for a while, but recently

a todoxy user asked me

What units does the "Estimate" field accept?

More...

My response was

The estimate field is purposefully unit-less. That's because the estimate field gets used in determining how much you can get done in a week, so you could think of it in hours, minutes, days, socks, difficulty, rainbows, or whatever -- just as long as in the same list you always think of it in the same terms.

A while back, Jeff Sutherland (one of the inventors of the Scrum development process) pointed out some of the reasons why story points are better than hours. It boiled down to four reasons:

- We are bad at estimating hours, but more consistent with points

- Hours tell us nothing since the best developer on the team may be multiple times faster than the worst

- It takes less time to estimate in points than hours

- "The management metric for project delivery needs to be a unit of production [because] production is the precondition to revenue ... [and] hours are expense and should be reduced or eliminated whenever possible"

But I noticed another benefit in my personal habits. Not only does it free us of the shackles of thinking in time and the poor estimates that come as a result, it corrects itself when you make mistakes.

I recognized this when I saw myself giving higher estimates for work I didn't really want to do. Like a contractor multiplying by a pain-in-the-ass factor for her worst customer, I was consistently going to fib(x+1) in my estimates for a project I wasn't enjoying.

But it doesn't matter. My velocity on that list has a higher number than on my other list, so if anything I hurt myself by committing to more work on it weekly for any items that weren't inflated.

What do you think about estimating projects in leprechauns?

Posted by Sam on Mar 31, 2008 at 12:00 AM UTC - 6 hrs

An interesting discussion going on over at programming reddit got me thinking about what features I'd like my ideal job to have.

Aside from " an easy, overpaid job that will get bring me fame and fortune," here's what would make up my list:

-

Interesting Work:

You can only write so many CRUD applications before the tedium drives you insane, and you think to yourself, "there's got to be a better way." Even if you don't find a framework to assist you, you'll end up writing your own and copying ideas from the others. And even that only stays interesting until you've relieved yourself of the burden of repetition.

Having interesting work is so important to me that I would contemplate a large reduction in income at the chance to have it (assuming my budget stays in tact or can be reworked to continue having a comfortable-enough lifestyle, and I can still put money away for retirement). Of course,the more interesting the work is, the more of an income reduction I could stand.

Fortunately, interesting work often means harder work, so many times you needn't trade down in salary - or if you do, it may only be temporary.

The opportunity to present at conferences and publish papers amplifies this attribute.

-

Competent Coworkers: One thing I can't stand is incompetence. I don't expect everyone to be an expert, and I don't expect them to know about all the frameworks and languages and tricks of the trade.

I do expect programmers to have basic problem solving skills, and the ability to learn how to fish.

-

Sane Management: Don't make me delighted to have a broken watch. I shouldn't have to turn back the dial on it to meet deadlines. Or put more strongly, management/customers shouldn't be given the latitude to control all three sides of the iron triangle of software development.

Scope, Schedule, and Resources. Choose two. We, the development team, get to control the third.

-

Trust: One comment in the reddit discussion mentioned root access to my workstation and it made me think of trust. If you cannot trust me to administer my own computer, how can you trust me not to subvert the software I'm writing?

Additionally, I need you to trust my opinion. When I recommend some course of action, I need to know that you have a good technical reason for refusing it, or a good business reason. I want an argument as to why I am wrong, or why my advice is ignored. If you've got me consistently using a hammer to drive marshmallows through a bag of corn chips, I'm not likely to stay content.

I don't mind if you verify. In fact, I'd like that very much. It'll help keep me honest and vigilant.

-

Personal Time: I like the idea of Google's 20% time. I have other projects I'd like to work on, and I'd like the chance to do that on the job. One thing I'd like to see though, is that the 20% time is enforced: every Friday you're supposed to work on a project other than your current project. It'd be nice to know I'm not looked down upon by management as selfish because I chose to work on my project instead of theirs.

I wouldn't mind seeing something in writing about having a share of the profits it generates. I don't want to be working on this at home and have to worry about who owns the IP. And part of that should allow me to work on open source projects where the company won't retain any rights on the code I produce.

-

Telecommuting: Some days I'll have errands to run, and I dislike doing them. I really dislike doing them on the weekends or in the evenings after work. I'd like to be able to work from home on these days, do my errands, and work late to make up for it. It saves the drive time on those days to help ensure I can get everything done.

There are some other nice-to-have's that didn't quite make the list above for me. For example, it would be nice to be able to travel on occasion. It would also be nice to have conferences, books, and extended learning in general paid for by the company. I'd like to see a personal budget for buying tools I need, along with quality tools to start with.

But if you can meet some agreeable combination of the six qualities above, I'll gladly provide these things myself. If you won't let me use my own equipment, and you provide me with crap, we may not have a deal.

That's my list. What's on yours?

Posted by Sam on Nov 13, 2010 at 10:34 AM UTC - 6 hrs

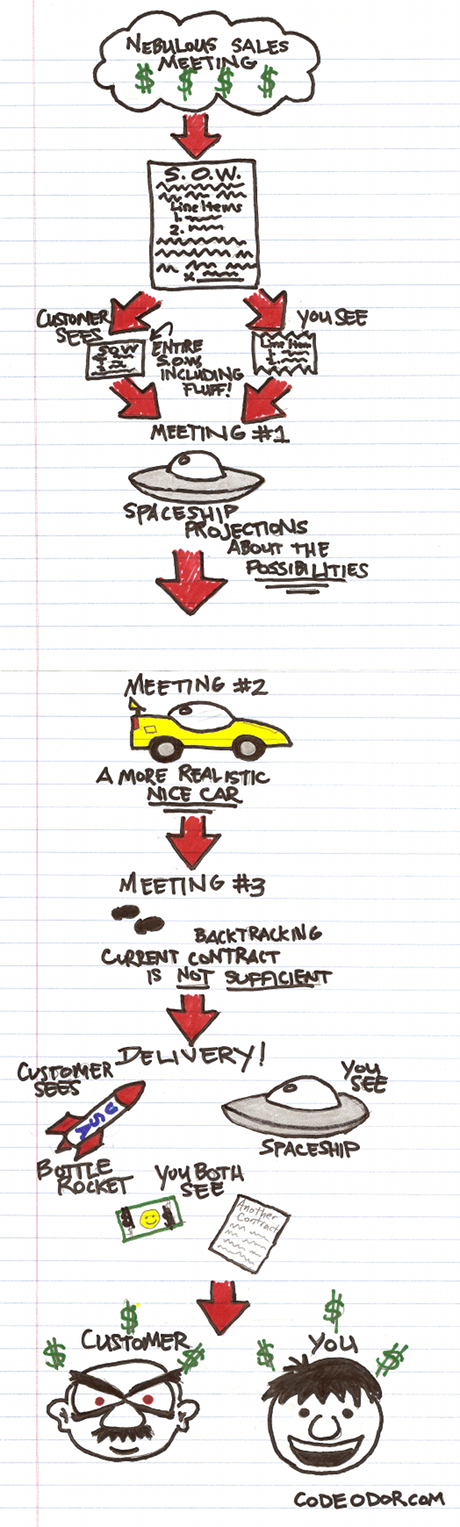

Focus on your customer's feelings, be clear about deliverables, and if you don't intend to deliver the fluff, don't talk about it as if you do.

Don't design contracts and project meetings around making yourself feel warm-and-fuzzy. Stroking your ego like this makes you feel like a hero who under-promised and over-delivered. Unfortunately, the customer got the opposite impression.

How is it that two groups of people experienced the same phenomenon, yet come away interpreting it world's apart?

Miscommunication and failure to manage expectations.

If you fail to communicate and verify what was understood was what you intended to say, you're liable to set expectations much higher than you can possibly deliver. That leads to pissed-off customers, or worse: past customers.

Posted by Sam on Jul 23, 2008 at 12:00 AM UTC - 6 hrs

Aside: It was tempting to satisfy my desire to entitle a blog post using two clichéd proverbs and an OrColon: Subtitle, but I refrained from calling this "Bad Apples Don't Always Spoil The Bunch, Or: Don't Throw The Baby Out With The Bathwater." I also could have used the subtitle, "Or: A Four Course Meal To Avoiding Disaster On Your Team." Such titles are great for posting to reddit/programming, but I've had enough cheese today on my pizza.

However, so that I don't neglect the cheese lovers among us who have a craving for the moldy substance, I'll tide you over with this morsel:

Mmmmmmm...

Appetizer entertainment from The Osmond's aside, we can get to the salad plate of our four course meal: Jeff Atwood wrote a blog post about Dealing With Bad Apples where he quotes some of Steve McConnell's work:

If you tolerate even one developer whom the other developers think is a problem, you'll hurt the morale of the good developers. You are implying that not only do you expect your team members to give their all; you expect them to do it when their co-workers are working against them.

He goes on to quote McConnell's reporting of the data (something valuable McConnell always offers):

In a review of 32 management teams, Larson and LaFasto found that the most consistent and intense complaint from team members was that their team leaders were unwilling to confront and resolve problems associated with poor performance by individual team members. (Larson and LaFasto 1989).

All of that is to say: software developers with bad attitudes should not be tolerated for long, lest they destroy the team from the inside.

He continues, citing ways in which to identify miscreants on your team, finally concluding that

You should never be afraid to remove -- or even fire -- people who do not have the best interests of the team at heart. You can develop skill, but you can't develop a positive attitude. The longer these disruptive personalities stick around on a project, the worse their effects get. They'll slowly spread poison throughout your project, in the form of code, relationships, and contacts.

There's nothing too striking here. In fact, I didn't think twice about it until I read Brian Cunningham's response:

I agree with this wholeheartedly. But you also have to ask yourself whether there's something you could have done to prevent things from getting to this point.

...

Whenever a bad apple is discovered on your team, you should always consider the possibility that it could have been prevented. In many cases there's nothing you can do -- it's simply a conflict of personalities. But if you find situations where the bad apple could have been prevented, that means there's something in the management of the team that needs to be addressed. (Strong emphasis mine)

And then Jeff's words stuck out, reminding me of me:

You can develop skill, but you can't develop a positive attitude.

In my case, it was me who decided to develop the positive attitude. But that doesn't mean it couldn't have been developed by a skilled manager who noticed the problem.

Retrospective action is useful in avoiding the problems of today in the future, but often misunderstandings, miscommunication, and a lack of clear goals or motivation can be the cause of friction or a bad-apple attitude.

So I take it a step further to the main course of our meal: Not only should you reflect on how the problem could have been averted upon discovery of the subversive, you should actively scan for potential problems and address them before they germinate.

It would not result in firings or team destructions, but instead focus on resolving the conflicts before they fully emerge. (Of course, if the problem is allowed to grow and fester, firings are encouraged.)

I'm not sure how to do that.

I don't personally have the answers regarding strategies for identifying problems and understanding what people really mean in conflict resolution, but I'm confident they exist. I've read as much. But I searched the all-knowing Google and didn't find the sources I sought. So at the moment, they remain outside

my realm of knowledge. Therefore, I'd like to ask: What are your strategies? How do you handle problem developers or teammates? What are the reading materials discussing these issues that I'm looking for?

More...

I supplied the dinner. Can you provide us with dessert?

Posted by Sam on Sep 04, 2008 at 12:00 AM UTC - 6 hrs

Outsourcing is not going away. You can delude yourself with myths of poor quality

and miscommunication all you want, but the fact remains that people are solving

those problems and making outsourcing work.

As Chad Fowler points out in

the intro to the section of MJWTI titled "If You Can't Beat 'Em", when a

company decides to outsource - it's often a strategic decision after much deliberation.

Few companies (at least responsible ones) would choose to outsource by the seat of their pants, and then change their

minds later. (It may be the case that we'll see some reversal, and then more, and then less, ... , until an equilibrium is reached - this is still new territory for most people, I would think.)

Chad explains the situation where he was sent to India to help improve the offshore team there:

If [the American team members] were so good, and the Indian team was so "green," why the hell

couldn't they make the Indian team better? Why was it that, even with me

in India helping, the U.S.-based software architects weren't making a dent

in the collective skill level of the software developers in Bangalore?

The answer was obvious. They didn't want to. As much as they professed

to want our software development practices to be sound, our code to be

great, and our people to be stars, they didn't lift a finger to make it so.

These people's jobs weren't at risk. They were just resentful. They were

holding out, waiting for the day they could say "I told you so," then come

in and pick up after management's mess-making offshore excursions.

But that day didn't come. And it won't.

The world is becoming more "interconnected," and information and talent crosses borders easier than it has in the past.

And it's not something unique to information technologists - though it may be the easiest to pull-off in that realm.

So while you lament that people are losing their jobs to cheap labor and then demand higher minimum wages, also keep in mind that you should be trying to do something about it. You're not going to reverse the outsourcing trend with

any more success than record companies and movie studios are going to have stopping peer-to-peer file sharing.

That's right. In the fight over outsourcing, you, the high-paid programmer, are the big bad RIAA and those participating in the outsourcing are the Napsters. They may have succeeded in shutting down Napster, but in the fight against the idea of Napster, they've had as much strategic success as the War on Drugs (that is to say, very little, if any). Instead of fighting it, you need to find a way to accept it and profit from it - or at least work within the new parameters.

How can you work within the new parameters? One way is to " Manage 'Em." Chad describes several characteristics that you need to have to be successful with an offshore development team, which culminates in a "new kind" of

PM:

What I've just described is a project manager. But it's a new kind of project

manager with a new set of skills. It's a project manager who must act at

a different level of intensity than the project managers of the past. This

project manager needs to have strong organizational, functional, and technical

skills to be successful. This project manager, unlike those on most

onsite projects, is an absolutely essential role for the success of an offshore-developed

project.

This project manager possesses a set of skills and innate abilities that are

hard to come by and are in increasingly high demand.

It could be you.

Will it be?

Chad suggests learning to write "clear, complete functional and technical specifications," and knowing how to write use cases and use UML. These sorts of things aren't flavor-of-the-month with Agile Development, but in this context, Agile is going to be hard to implement "by the book."

Anyway, I'm interested in your thoughts on outsourcing, any insecurities you feel about it, and what you plan to do about them (if anything). (This is open invitation for outsourcers and outsourcees too!) You're of course welcome to say whatever else is on you mind.

So, what do you think?

Posted by Sam on Mar 05, 2010 at 10:14 PM UTC - 6 hrs

You might think that "tech support" is a solved problem. You're probably right. Someone has solved it

and written down The General Procedures For Troubleshooting and How To Give Good Tech Support.

However, surprisingly enough, not everyone has learned these lessons.

And if the manual exists, I can't seem to find it so I can RTFthing.

The titles of the two unheard of holy books I mentioned above might seem at first glance to be

different tales. After all, troubleshooting is a broad topic applicable to any kind of

problem-solving from chemistry to mechanical engineering to computer and biological science.

Tech support is the lowliest of Lowly Worms for top-of-the-food-chain programmers.

More...

(And don't ask me how sad it makes me feel that my favorite book as a kid has only a 240px image online. I need to find my copy and scan it.)

(And don't ask me how sad it makes me feel that my favorite book as a kid has only a 240px image online. I need to find my copy and scan it.)

But just like its more enlightened brethren, tech support consists of troubleshooting. In fact, it should be

the first line of defense to keep your coders coding and off the phone. Who wants them to man the phones?

Certainly not the programmers. Certainly not management. Tech support is a cost center, not a customer

service opportunity.

That's a lie of course. It's a bajillion times more likely that you'll sell to an existing customer than someone else1.

So why do we see such poor customer service? Especially in our own industry?

Perhaps when you have a virtual monopoly over a market like most cable companies or utilities in a given locale,

you can afford to have poor customer service. The cable sphere seems to be opening up, what with satellite TV and internet

and now AT&T and Verizon offering television and decent-to-good internet packages.

Even still, AT&T's UVerse has its own problems, I've heard,

and (at least personally) I've not witnessed the kind of customer service that competition promises with regards to cable TV and internet access.

Is tech support really that bad? Maybe it's not. There are some folks

that have decent starting advice. Even if it's not How To, at least Some Ways is better than no ways.

The fact is we tend to treat support like a second class citizen. It's a position we want to fill with a minimum-wage worker (or less, if we

can outsource it) who has no expertise, no clue, and doesn't care to learn the

product since he can get a job in the fast food industry at about the same rate. And with no stress!

It makes it worse that we don't even want to take the time to train him, since it would take away from the productive code-writing time to do so.

The person we want to treat as an ape or worse always seems expendable. We treat them so. Should they be?

I say no. Not only am I a big fan of dogfooding,

I feel like Fog Creek's

giving customer service people a career path nowadays

matches a lot of my ANSI artist peers' experiences

from back in the day. Smart people start in support, and they can move themselves up in the organization to play more "key roles."

Bill puts on a headset, sits down, and answers the phone. "Hello, this is Microsoft Product Support, William speaking. How can I help you?"

Bill talks with the customer, collects the details of the problem, searches in the product support Knowledge Base, sifts through the search results, finds the solution, and patiently walks the customer through fixing the problem.

The customer is thrilled that William was able to fix the problem so quickly, and with such a pleasant attitude. Bill wraps up the call. "And thank you for using Microsoft products."

At no point did Bill identify himself as anything other than William. The customer had no idea that the product support engineer who took the call was none other than Bill Gates.

Like Bill.

I don't think it needs to be a full-time thing, but it certainly helps if programmers are their own support team.

Like Bruce Johnson who posted that linked message, I work on a small team and can vouch: it's downright embarrassing to have to support

our customers. I'm glad to do it, but when it happens, more than likely I've got to take blame for the problem I'm dealing with.

You know how hard I try to make sure my code works as expected before I deploy it?

"OMG I'm sorry, that's my fault, I'll fix it for you right away." Can you get better support than that?

I'm not so sure I'd have tried that hard without the customer experience pushing me.

I think I've made my first point: that customer support is customer service is important to the health of your business.

While I agree that tech support in the common use of the term is useful to shield your programmers from

inane requests, I also recognize the value in having programmers take those calls from time-to-time.

Given that, I do in fact have some do's and do-not's with regards to support. The list here deals mostly with

how to be a good support technician for your team, as opposed to the customer. Still, the customer is

central to the theory.

Although it does not make an exhaustive list, here are four contributions to The General Procedures For Troubleshooting:

-

After listening to the problem description, the first thing to do is recognize whether or not you can

solve the problem while the customer is on the phone, or if anyone can. If you can, then do it. If you think

only someone else can do it, and work for an organization that has multiple levels of live-support, then escalate it.

If you don't think solving the problem is possible without escalating it to a level of support that won't get

to it immediately, thank the customer for reporting the issue, let them know the problem is being worked on,

and boogie on to step 2.

- As support, the first thing you need to do before escalating the issue is confirm there is an issue, and do it with a test account, not the user's.

It's ridiculous to ask for the user's

credentials. Don't do it. If someone were to ask you, "What is your username and password?" what would you think?

The average user isn't going to know your query is tantamount stupidity, but if you get someone who is slightly

security-conscious, you're going to lose a customer. Hopefully, he's not a representative of your

whale.

If anyone found out that you're in the habit of asking users for their passwords, they can easily call anyone

who uses your software and get in by just asking. Further, since many people use the same password for everything

or many things, that person would also have access to your customers' other sensitive information, wherever it resides.

You can point the blame at your stupid customer for using the same password everywhere they go all you want. You're being

just as stupid by opening the door for that type of attack. Further, you should always try to recreate and fix the problem

with as little inconvenience to the user as possible. That means doing it with test accounts as opposed to asking the

user for theirs, or changing their information.

Keep things simple for the user. Don't jump immediately to using their time to make things easier on the support team.

Doing that is lazy at best, sloppy most of the time, and could result in disaster at worst.

- After confirming the existence of the problem, provide the steps of how to reproduce it. Give some screen shots.

If it's a web app, provide links. Don't constantly send and email and ask the higher levels about it. Doing so once or twice is

one thing, but doing it for every request is a time-waster. Just send the email and the next level will get to it

when they can. If they don't get to it within the acceptable time-frame for your organization, send a reminder.

Include the boss if you need to. But don't do that prematurely (and that's another subject altogether).

-

Don't jump to conclusions about the source of the problem.

Although Abby Fichtner wasn't speaking

directly to support ...

... This is the opposite of my general approach. The parallel here is code : customer :: you : dumb2.

I've learned (even if through a bit of self-torture) that I should always look at the code first, if for no other reason than I don't

want to be foolishly blaming others when I'm to blame. In the case of support, I've always hated the term "User Error,"

and that's what the tweet reminds me of.

By framing it as an external problem, we miss an opportunity to teach the user how to use the product, or a chance to

improve the product to make sure they can't use it "incorrectly."

What are your thoughts about tech support? What can you contribute to The General Procedures For Troubleshooting?

Notes:

1) I know this statistic, it's even intuitive, but I can't seem to find it online for free.

Here's some apparently made-up stats to satisfy you.

Go back to what you were reading.

2) "word1 : word2 :: word3 : word4" is SAT (and elsewhere) notation for

the analogy "word1 is to word2 as word3 is to word4." See freesat1prep.com

for a few examples.

Some links in this post are affiliate links. This message brought to you by the Federal Trade Commission.

Last modified on Mar 24, 2010 at 10:57 AM UTC - 6 hrs

Posted by Sam on Feb 06, 2010 at 10:36 AM UTC - 6 hrs

There was once upon a time I held some affinity for Expert'sExchange.

I tried hard and succeeded at becoming an expert. I thought it might look good on a resume and in fact

I got a few offers of job and freelance work from it.

More...

I was an expert at ColdFusion.

A couple of the guys who I remember racing for "the right answer" are still up there, including one who came after the

guys who came after the guys who came after Dain

" OMFG do they really have a book on ACM?" Anderson. You might know

him. It might be from cfcomet fame.

(I have no clue why my email address from back then says I have no account,

nor do I know why I'm no longer listed in the top experts even though I ha(d/ve) the points).

I used to give EE ideas

on how to make their service better. I don't mean to sound like an ideaman -- I know ideas are only worth something

when they're executed -- but I told them I'd implement the ideas for them. A simple one that I harped on was: instead of

getting X number of email notifications on a question, send me the first one, and only send me subsequent emails if I've logged in.

This was before RSS days, so I had no way to stay up-to-date without it

(or shittons of irrelevant emails).

It wasn't a hard thing to implement. It didn't matter though: my suggestions fell on deaf ears.

And the site, as you know, tried to maximize earnings while ensuring

it's audience remained pissedoffandalienated.

That's right, when I stopped contributing, EE became an outhouse on the web. I take full credit: when I left,

EE began its downfall.

Seeing as you're reading this blog, chances are that you're a programmer.

Being such, you probably know how evil ExpertS-exchange became. You (used to) google for a problem,

and more often that not, some spammy BS from that site would show up. If you were savvy and

in-the-know, you'd not have clicked on it. And if you didn't happen to be paying attention, you'd

realize you made that gawdawful click when you saw the page loading, and immediately scroll

to the bottom to see the answer.

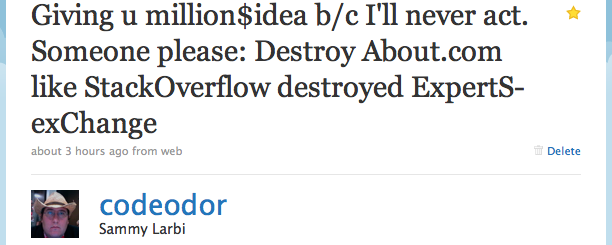

It was ripe for ripping and easy to pick off. That's a 20-20 hindsight thought. StackOverflow

is in the process of taking over EE (if

it hasn't by the time you read this). Thankfully.

But the two programmers' questions websites are incidental to this story. Actually, this story is more about business, and

recognizing a market and capitalizing on it.

A little while ago, I was looking for content to embed in a high-school course. I thought,

It's still true. But then,

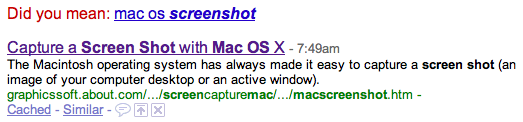

at the time of this writing, I was looking for the non-clipboard-screenshot-save-as-file keyboard shortcut on MacOSX.

It looks like a pattern. But it's not yet.

Even though I already play guitar, I was wondering about how I might teach it to my daughter. I was self-taught, so I don't know how I'd go

about teaching someone else without feeling like I've crippled them. Later, after spending the evening with teachers and principals,

I was thinking about how they accommodate gifted kids.

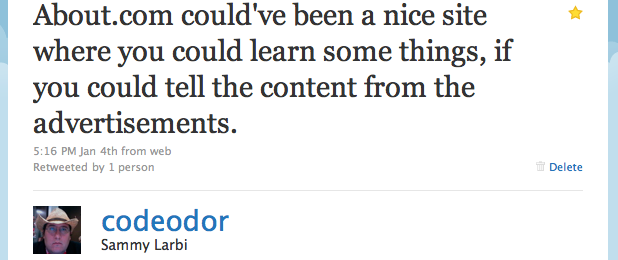

As you can tell, it doesn't matter what I think. It doesn't matter what you think. About.com comes up in all these (seemingly?)

random cases as an authority answer to the question. What's worse: it's hard enough to tell the ads from the content for

someone you'd expect to be savvy on that. Can you imagine the hardship a "normal person" would suffer?

If it's not obvious now, the million dollar idea is to do to About.com what StackOverflow did to Experts-Exchange.

I assume About.com has some good content, but it's too hard to tell by looking at it. The position is ripe for the picking.

Create an unspamalicious About.com and you're rich.

Tell me about it if you make the attempt. I'll link it here.

Last modified on Feb 06, 2010 at 10:37 AM UTC - 6 hrs

Posted by Sam on Nov 12, 2009 at 09:38 AM UTC - 6 hrs

We observe that organizational structure metrics are significantly better predictors for identifying failure-prone binaries in terms of precision, and recall compared to models built using code churn, code complexity, code coverage, code dependencies, and pre-release defect measures.

(Link is to abstract page, quote is from the PDF linked to from there, chart below is from the paper as well)

More...

Further research needs to be carried out to see if this generalizes beyond the Windows Vista team.

Needless to say, it's not a license to write crapcode, as those metrics are still good predictors of software defects, but it's interesting to note just how important organization is to software quality.

Thoughts?

Thanks to Sean Corfield for bringing the paper to my attention.

Last modified on Nov 12, 2009 at 09:38 AM UTC - 6 hrs

Posted by Sam on Mar 24, 2009 at 12:00 AM UTC - 6 hrs

Every day, psychological barriers are erected around us, and depending on what task they are a stumbling block for,

they can be helpful or a hindrance.

Ramit Sethi wrote a guest post on personal finance blog Get Rich Slowly about passive barriers that got me

thinking about passive barriers in software development, or perhaps just any easily destroyed (or erected barrier) that

prevents you from doing something useful (or stupid). One example he uses that comes up a lot in my own work

references email:

More...

I get emails like this all the time:

"Hey Ramit, what do you think of that article I sent last week? Any suggested changes?"

My reaction? "Ugh, what is he talking about? Oh yeah, that article on savings accounts ... I have to dig that up

and reply to him. Where is that? I'll search for it later. Marks email as unread"

Note: You can yell at me for not just taking the 30 seconds to find his email right then, but that's exactly

the point: By not including the article in this followup email, he triggered a passive barrier of me

needing to think about what he was talking about, search for it, and then decide what to reply to.

The lack of the attached article is the passive barrier, and our most common response to barriers is to

do nothing.

(Bold emphasis is mine).

If I can't immediately answer an email, it gets put on hold until I have time to go through and do the research

that I need to do to give a proper reply. Sometimes, that means your email never gets answered because eventually

I look down at the receipt date and say to myself "I guess it'd be stupid to respond now." But I digress.

In everyday software development, there are a number of barriers that can help us:

-

Minimizing or closing the browser. When a compilation is expected to take up to a minute, or a test suite

will run for too long, or a query takes forever, there's not much work that can be done, so I might

fire up the feed reader, email, or twitter to pass the time away. The problem here is that you'll often spend

far longer on your excursion than it takes for your process to complete. If you waste just 5 minutes each time,

you've accomplished nothing - you're just skimming and certainly not getting anything out of it, and you could

have been back working on what you were trying to accomplish. In these situations, I have my email, feed reader,

and twitter minimized, and that significantly reduces the urge to open them up and start a side quest.

If you wanted to get more to the active side of barriers, you might just add the line

to your hosts file. That turns a passive barrier to time waste into a downright pain.

-

Having a test suite with continuous integration and code analysis tools running. At various points in a day you might be tempted to

check in code that breaks the build or introduces a bug. This is especially true at the end of the day.

However, if you have a test suite that runs on every commit, you're much more likely to run it to avoid the embarrassment of checking

in bad code. If you've got static analysis tools that also report on potentially poor code, you're less

likely to write it.

-

Annoyance Driven Development. This isn't one that I know how to turn on or off, but I think it would be

a great feature to have in IDEs or text editors: it gets slow when your methods or classes or files get too big.

This would be a great preventative tool, if it exists. I guess it falls back to using test suites and

code analysis to provide instant feedback that annoys you into doing the right thing.

-

Working with others, or having others review your code. Most of us pay more attention to quality

when we know others will be looking at the code we write. Imagine how much more of your code you'd be

proud to show off if you just knew that someone would be looking at it later.

Just as well, there are also barriers that hinder us:

-

Interruptions. This one is obvious, but so pervasive it should be mentioned. IM,

telephone calls, email, coworkers stopping by to chat or ask questions - they all prevent us from working

from time to time. The easy answer is to close these things, and that's what I do. They all represent

passive barriers to getting work done, and you can easily turn that around to be a passive barrier

against wasting time (see above). Pair programming is an effective technique that erects its own

barrier to these time wasters.

If you're really looking for something to help you focus, I'd have a look at The Pomodoro Technique,

which divides your work into tomato time units of 25 minutes each, which really helps you focus on work. It's

agile for time management. (The Pomodoro Technique PDF book is available for free.)

-

Rotting Design: Rigidity, Fragility, Immobility, and Viscosity. Bob Martin discusses these

in his (PDF) article on Design Principles and Design Patterns. Quoting him for the

descriptions, I'll leave it to you to read for the full story:

Rigidity is the tendency for software to be difficult to change, even in

simple ways. Every change causes a cascade of subsequent changes in dependent

modules. What begins as a simple two day change to one module grows into a multi-

week marathon of change in module after module as the engineers chase the thread of

the change through the application.

...

Closely related to rigidity is fragility. Fragility is the tendency of the

software to break in many places every time it is changed. Often the breakage occurs

in areas that have no conceptual relationship with the area that was changed. Such

errors fill the hearts of managers with foreboding. Every time they authorize a fix,

they fear that the software will break in some unexpected way.

...

Immobility is the inability to reuse software from other projects or

from parts of the same project. It often happens that one engineer will discover that he

needs a module that is similar to one that another engineer wrote. However, it also

often happens that the module in question has too much baggage that it depends upon.

After much work, the engineers discover that the work and risk required to separate

the desirable parts of the software from the undesirable parts are too great to tolerate.

And so the software is simply rewritten instead of reused.

...

Viscosity comes in two forms: viscosity of the design, and viscosity of

the environment. When faced with a change, engineers usually find more than one

way to make the change. Some of the ways preserve the design, others do not (i.e.

they are hacks.) When the design preserving methods are harder to employ than the

hacks, then the viscosity of the design is high. It is easy to do the wrong thing, but

hard to do the right thing.

The point is that poor software design makes an effective barrier to progress. There are only two ways

I know to tear down this wall: avoid the rot, and make a conscious decision to fix it when you

know there's a problem. There are plenty of ways to avoid the rot, but books are devoted to them, so

I'll leave it alone except to say a lot of the agile literature will point you in the right direction.

-

Unit Tests. I struggled with the idea of putting this on here or not. If you're an expert, you already know this.

If you're a novice or lazy, you'll use it as an excuse to avoid unit testing. The point remains: unit testing

can be a barrier to producing software, if you are exploring new spaces and having trouble determining

test cases for it. I'll let the Godfather of TDD, Kent Beck, explain:

... I still didn't have any software. As with any speculative idea, the chances that this

one will actually work out are slim, but without having anything running, the chances are zero. In six

or eight hours of solid programming time, I can still make significant progress. If I'd just written

some stuff and verified it by hand, I would probably have the final answer to whether my idea is

actually worth money by now. Instead, all I have is a complicated test that doesn't

work, a pile of frustration, eight fewer hours in my life, and the motivation to write another essay.

These are just a few examples, so I'm interested in hearing from you.

What barriers have you noticed that positively affect your programming? Negatively?

Posted by Sam on Mar 30, 2009 at 12:00 AM UTC - 6 hrs

A friend of mine from graduate school recently asked if she could use me as a reference on her resume.

I've worked with her on a couple of projects, and she was definitely one of the top few people I'd

worked with, so I was more than happy to say yes.

Most of the questions were straightforward and easy to answer. However, one of the potential questions

seemed way off-base: I may be asked to "review her multi-tasking ability."

Is that a trick question? Is it relevant?

More...

Of course I want to paint her in the best possible light, and in that regard, I'm unsure how to answer such

a question. Why? To understand that, we need to ask

What's the question they're really asking?

There are two disparate pieces of knowledge they can hope to glean from my answer to that question:

- Does she concentrate on a single item well enough to finish it?

In this case, they are asking the opposite of what they want to find out. The trick relies on the reviewer to give

an honest opinion, whereas most people would assume they should answer each question in the affirmative. Because

the rest of the questions seem straightforward, I'd give this potential "real question" a low

probability of being what they really want to know.

-

Is the candidate able to juggle multiple different projects and work effectively?

I give this one the higher probability of being the question the employer really wants the

answer to. But it's a ridiculous question. On the one hand, you already know the job candidate has

successfully completed two levels of college, so it should be clear that they can handle multiple different

projects given the appropriate resources. On the other hand, I don't think they care about the

"appropriate resources" part. I think they're setting their employees up to fail because they

don't understand that

Multitasking can result in time wasted due to human context switching and apparently causing more errors due to insufficient attention.

Is "multitasking ability" just code for unable to accomplish anything because you require employees

to work on so many different projects in parallel that progress cannot be made on any of them?

Is "multitasking ability" just code for unable to accomplish anything because you require employees

to work on so many different projects in parallel that progress cannot be made on any of them?

What's your opinion?

Update: John G. Miller (or someone claiming to be him) is author of a book and has asserted trademark rights to a phrase originally used in this article, so I've removed it.

Posted by Sam on Nov 04, 2009 at 08:45 AM UTC - 6 hrs

A great development team is an asset that gains you competitive advantage in the marketplace. They

churn out features quicker than other teams, with higher quality code that contains fewer defects.

You give them project after project and they routinely meet or exceed the deadline.

They're well known for hitting on all cylinders often enough to pull off seemingly miraculous feats

of software engineering.

More...

All is right in your world.

It's relieving to know you have a team you can trust, and your team members take pride in knowing

that you believe so highly in their skills that you rely on them in the squirreliest of

circumstances.

The pitfall shows itself when, instead of enjoying the benefits of such a team, you start to rely

on those benefits. You start to assume the "firing on all cylinders" is the norm, and schedule accordingly. You

let yourself believe those miraculous deliveries means you can put off important decision making until a

week before they need to be delivered.

As long as everything goes good, you're in the clear. And it normally does. But what happens if someone

gets sick or has a family emergency to attend to? What happens if your team just can't maintain that

sort of intensity indefinitely?

You're going to be late. What's worse is you needn't have been so if you would have

remembered to plan for things like that.

It's just a word of caution: don't assume perfection, even if empirical evidence suggests otherwise.

Last modified on Nov 04, 2009 at 08:46 AM UTC - 6 hrs

Posted by Sam on May 14, 2009 at 12:00 AM UTC - 6 hrs

Many people see spectacular plays from athletes and think that the great ones are the ones making those plays.

I have another theory: It's the lesser players who make the "great" plays, because thier ability doesn't take them

far enough to make it look easy. On top of it all, you could say guys who make fewers mistakes just

aren't fast enough to have been in a position to make the play at all.

More...

In the case of sport, one might also make that argument against the lesser players in favor of the ones who

regularly make the highlight reel: their greatness lets them get just a tad closer, which allows them to make the play.

In the case of software development, that case is not so easily made.

When developers have to stay up all night and code like zombies on a project that may very well be on

a death march, you've got a problem, and it's not solely that your project might fail. Even when that super heroic

effort saves the project, you've still got at least three issues to consider:

- Was the business side too eager to get the project out the door?

- Are the developers so poor at estimating that it led to near-failure?

- Is there a failure of communication between the two sides?

In saving the project, the spectacular effort and performance of your team or individuals on your team is

not something to be marveled at - it's a failure whose cause needs to be identified and corrected.

Handing out bonuses is a nice way to show appreciation for their heroic efforts, but it encourages poor

practices by providing disincentives for doing the right thing:

- No incentive to make good estimates.

- Incentive to give in to distrations since they "can always just stay late"

- No reason not to have a foggy head half the day

- A motive for waiting until the last minute, just to show off their prowess

Handing out bonuses to the individuals who displayed the most heroism brings friction and

resentment from

those who opted to sleep (especially among those who realize half the work was created by the

heroes!).

Yet, having only part of the team on board with the near-death march causes the same resentment from the

sleepless hackers.

Rewards encourage repetition of the behavior that led to the prize. When you do that, you're putting

future projects in peril.

There are plenty of ways to reduce the risk and uncertainty of project delivery - and subtantially fewer

tend to work when you wait until the last week of a project - but those methods are the subjects of other stories.

What are your thoughts?

Posted by Sam on Aug 11, 2009 at 12:00 AM UTC - 6 hrs

The other day on twitter I asked about large projects, and I wanted to

bring the question to the larger audience here.

We hear vague descriptions about project size tossed about all the time:

Ruby on Rails is better for small projects. Java is for large projects. Skip the framework for

small projects, but I recommend using one for large projects.

More...

What factors go into determining the "size" of a project? Certainly lines of code and the size of the team are

considerations. Perhaps we should include the number of users as well. What would you add?

I suspect that to developers who tend to work alone on projects, a large one might be dozens of thousands of lines

of code. For those who work in moderate size teams, say with half a dozen members, we might hear a few hundred

thousand lines of code. For large teams in the teen-range, I'd expect millions of lines. What about teams with

50-100 developers?

I think makes a difference when you're giving advice on various aspects as to what constitutes a large project (or, if

you believe the advice is relative in those aspects, say why), so I'm interested to hear your thoughts.

So I ask, what is a "large project" to you? What do you think it means to others?

Posted by Sam on Aug 25, 2009 at 12:00 AM UTC - 6 hrs

Everyone will run into "that guy" on a project at some point in their lifetime.

He complains about everything, and he's actively trying to

subvert it at any given time. It seems like he had an agreement with another vendor to take a kickback, but they

didn't win the bid so he's stuck with you until he can prove your incompetence to the other stakeholders in

his organization.

At every turn, he's complaining about something. He's "spent hours on the phone" with you about a problem,

but you know you've only talked to him once for 5 minutes to get a password outside the normal meetings.

The normal meetings resulted in changing requirements and specifications as time went on,

and he never spoke up until that part of the product was complete. Now he says you're useless and

can't follow directions: he wants the original widget design back.

He's not the only stakeholder, but he's the stakeholder for certain parts of the project. Maybe his mini-projects

are just there to grease the wheels and facilitate other parts of the whole. Maybe it's a key part of the

end product.

There's an effective way to deal with bitchy subversives when you're at the meeting with everyone from

each side of each organization and "that guy" is making insane requests and ridiculous accusations. Simply

pose an open question for everyone to answer:

what about that piece is holding the rest of the project back?

Trying to answer that question will reveal that there's nothing technical that's holding it back. The only

thing holding back the project is that guy's whining.

Then you can move forward.

|

Me

|