Asking the right question

This post relays some wisdom from

Scott Davis's keynote speech at

NFJS

in Austin a little over a month ago. The talk was titled, "No, I Won't Tell You Which Web Framework to Use... (or The Truth, With Jokes)."

He talked about a lot of different things, but the point of the talk didn't really have anything

to do with web frameworks, or computers in general. It was about choice, markets, crowds, and questions.

It can be applied easily to the software we build, but it can also

be applied equally to other things in general. Well, at least that's what I came away with.

Scott first explained why asking "which web framework should

I use?" is virtually pointless. How

do I know what framework you should use? I don't know what you're looking for in it. I don't know what

you need it to do. Answering what

you should do based on my needs is "outside my realm of expertise."

All of them work, so "every framework out there is potentially the 'right one.'"

Instead, you should ask me "what framework do you use" or even better, "why do you use the framework that you do?"

Here he actually related it to cell phones, but I'll stick with the web framework theme. In fact, you could

replace web framework with

x, where x ∈ UsableNouns

and it would still make sense.

Choose? I've got too many stinking options!

At this point Scott started to explain analysis paralysis and brought up a new book to put on my to-read list:

The Paradox of Choice: Why More Is Less.

He told a story (I believe to be from the book) that succinctly showed what happens when

consumers are presented with too many choices: Given 3-5 options for tasting Jellies/Jams,

customers ended up buying more of it. However, increasing that to two-dozen left sales at levels

lower than having no sampling at all.

We simply become overwhelmed by the number of options available, turn off, and refuse to make a choice

at all. That leads us to the

Maximizer/Satisficer concept,

where the Maximizers are especially prone to analysis because they try to be more prepared when making decisions and

never stop analyzing, even after making the choice. On the other hand, satisficers try to

narrow their decision-making points down to a reasonable few.

The existence of analysis paralysis doesn't "mean that we should limit

the number of frameworks that can be legally created."

Instead, we should try to be like the satisficer and "limit

out decision criteria to 3-5 important attributes."

So which framework should I use?

Consider "Plain Old HTML." As Scott noted, "Nothing will scale better, nothing

is easier to deploy, [and] nothing is better supported across all vendors, servers, platforms, languages..."

Even without all that, "it forces you to identify what features you

really need." That,

according to Scott, is the most important reason to use plain HTML. In any case, make sure you

stick to standards so you can switch easily.

But the interesting part for me was not his discussion of web frameworks - it was the books he

mentioned while making his points (more to put on the to-read list!). Therefore, I'll focus more on that

aspect.

Scott brought up Struts - and while one might use

The Wisdom of Crowds

to justify its use, you might also notice its complexity is reminiscent of an older era and the leaders

of the movement have moved on to other things. It is past Struts 1.x time.

Struts 2 is out now, but it has thus far failed to reach

The Tipping Point.

On the other hand, Ruby on Rails illustrates the qualities of the tipping point: virally contagious,

"dramatic and immediate" effect, not "slow and steady." It shows how "tiny 'tweaks' to a proven model

can yield big, disproportionate effects." By introducing the concepts of convention over configuration,

scaffolding, and "opinion-oriented software" to the traditional MVC approach, Rails hit the

tipping point.

When to adopt new technology

Aside from narrowing your decision points and using the heuristic of the wisdom of crowds,

Scott introduced the Gartner Hype Cycle,

the O'Reilly Curve, and yet another book to go on my reading list,

Crossing the Chasm

to help explain the tipping point and give something to consider as to when you might want to

adopt a new technology.

Gartner

explains the Gartner Hype Cycle

well enough, so I'll leave it to you to learn from the source.

The O'Reilly Curve (Image from Scott Davis's presentation slides -

Couldn't find it online Online

here)

The O'Reilly Curve (as near as I can tell) was invented by

Doug Kaye

of

IT Conversations.

Basically, the idea is that "publication of an O'Reilly book signals a transition of that technology from 'innovation' to 'early adopter' phase."

Update: Thanks to Doug, you can read a full

discussion about the O'Reilly Curve at his blog.

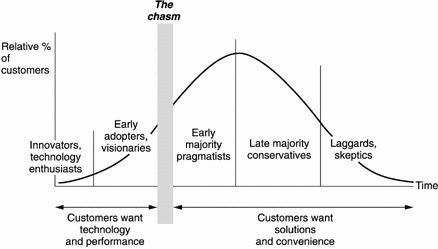

As you can see in the graph above, there are many stages to technology adoption.

Although you may want to

be an early adopter to increase your chance of success, you can see that you don't achieve

return on investment (as an organization) until after there are experienced staff available to

work in the new technology.

Before that, you have some lead-time that can bring you

competitive advantage.

So when is the best time to move in? If I recall correctly, Scott mentioned the same as Doug Kaye- when

O'Reilly publishes a book. That gives you enough resources to be successful, and enough lead-time

to be ahead of competitors. Of course, your acceptable level of risk and values will vary, so your choice ultimately

comes down to the type of person you are or organization you work in (also explained in

Gartner).

As our final heuristic, we can look at the chasm and ask ourselves, "Has the technology crossed it yet?"

Crossing The Chasm (Image from the book, I believe)

Thinking about these things is not only useful from a technology perspective, but from a sales and

marketing business perspective for your own products, which is what interests me more about them. (I don't have much

experience in those areas, which is why I'm putting these books on my to-read list.) Because of

that, I'll remain otherwise silent on the issue, only noting that you needn't look at them from one

perspective.

"You know that thing you think is a duck? Well I think it's a rabbit."

Scott said something like that when he began a discussion of paradigm shifts, noting that

Rails and Grails are "still fundamentally page-centric MVC frameworks." On the other hand,

JSF,

Seam, and

Tapestry

are based on the idea of component-widgets and are much more in line with the Web 2.0 paradigm shift.

(The book from this section that goes on my to-read list is

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,

which talks about paradigm shifts in science.)

Bringing it all together

You should be convinced that asking what framework you should use is a poor question.

You should be asking what other people use and "why?" As Scott reiterated at the end of his presentation,

"I can't tell you which filters to apply" when making your decision. But the key is found

in "thin-slicing" (from the final book I'll link to today,

Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking).

Thin-slicing is the act of "filtering on the few factors that matter" while "ignoring the overwhelming number

of others." Sound familiar? It should.

The point is that when making a choice about something, be it technology or otherwise, you need to

consider only what is relevant. Pick a few features you need, pick a level of adoption or risk you're willing to

handle, and consider shifting paradigms (will the well established still be around?). Ask someone

what they use and why they use it. Then, when you've narrowed the field of consideration to something

manageable, you can make your choice.

So, what framework I should use?

Hey! Why don't you make your life easier and subscribe to the full post

or short blurb RSS feed? I'm so confident you'll love my smelly pasta plate

wisdom that I'm offering a no-strings-attached, lifetime money back guarantee!

Leave a comment

Thanks Doug. I've updated the post accordingly so it's found a bit easier.

Posted by

Sam

on Aug 13, 2007 at 09:48 PM UTC - 6 hrs

"On the other hand, JSF, Seam, and Tapestry are based on the idea of component-widgets and are much more in line with the Web 2.0 paradigm shift."

No, I dont think so. Web 2.0 is about REST-centric. Component-based framework try to be desktop-alike environment. It is not web-oriented.

Posted by pcdinh

on Aug 14, 2007 at 04:36 AM UTC - 6 hrs

pcdinh- Thanks for the valuable comment. Let me ask you some more questions and raise some more points below.

Is what we mean by Web 2.0 just that it is "REST-centric?" I think that's certainly part of it, but what about the ideas of community and Ajaxification? There are probably others, but those are 3 that are on the top of my head. In fact, I would have thought being REST-centric was a relatively minor item.

In any case, my thought is that the other two I mentioned are also large parts of the paradigm shift to Web 2.0, and componentization (can I call it that?) plays well idea-wise with Ajax. In other words, now we might think of widgets talking back and forth with the server rather than thinking in terms of pages.

I know the idea of component-based frameworks was to try to be like desktop programming - insulating you from the underlying fact you are on the web - but I don't see how that is fundamentally different from thinking in terms of components instead of pages.

Of course, I've yet to use those frameworks, so I'm really just basing that on semantic understanding of the words chosen to represent the technology, not on any deep understanding of the frameworks themselves.

Thoughts?

Posted by

Sam

on Aug 14, 2007 at 08:53 AM UTC - 6 hrs

I think that there is no relationship between component based frameworks and Web 2.0 at all. Maybe they are both popular these days, but their development has been independant from each other.

In my opinion JSF was surprised by the success of AJAX and would look quite different if the commitee had AJAX support during development in mind .

Posted by Anon

on Aug 14, 2007 at 06:37 PM UTC - 6 hrs

@Anon - It may be that there is no relation between the two. I'll defer to your judgment since I haven't used a component based framework. =)

But I will point out that simply because their respective developments have been independent is not cause to believe they are not part of the same movement/paradigm shift. In fact, I think if we look at history most such shifts in thinking have occurred by independent actors in a given time frame.

Such shifts occur when we take into account many different developments that change our attitudes and beliefs.

Posted by

Sam

on Aug 15, 2007 at 10:40 AM UTC - 6 hrs